Just Think About it, and Generative AI Will Do The Rest for you. A New Generative Reality based on Actor-Network Theory (ANT)

Consider something you would like to create, recreate or imitate (art, photos, videos, music, stories, coding, a deepfake of a prime minister etc.), and generative AI will be happy to assist you. Does this mean that we have reached an era where saying just a few words enables you to create or replicate almost anything you can imagine (pretty much like a utopian science fiction novel)? And, for which price are we willing to have this assistance?

This blog post will briefly summarise what generative AI is, and can do, its multiple types (i.e. Generative Adversarial Networks - GANS), how this differs from traditional AI, and its benefits and risks. We will conclude with a short introduction to Actor-Network Theory (ANT) by Bruno Latour as a theoretical and methodological approach to account for the relational nature of the society. Actors, in this theory, are not just humans or collectives of humans. Technical objects or artificial agents such as GANs, a class of deep neural network models able to simulate content with extreme precision, are also considered by ANT equally significant for the circulation of contents, beliefs and information inside a social system. GANs, have been primarily used to create media simulating human beings conveying politically-relevant content.

What is Generative Artificial Intelligence?

To what extent can we say AI can assist us in almost any task? In the face of the latest advancements in AI, the list of such tasks seems to be diminishing almost daily. Furthermore, even though we are still far away from achieving Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) or "Human-Level AI", as

Kurzweil

(2005) would say, recent advancements in the sub-fields of AI, such as Natural Language Processing (giving computers the capacity to understand the text and spoken), and Computer Vision (computers see, observe, and 'understand), have shown that we are not the only ones capable of instantly and creatively generating images, videos, stories, music, or code from just a short text. This hype around generative technologies has been developing around tech giants such as Elon Musk with its DALL·E

Open AI

text-to-image technology.

We can sub-divide generative AI's three famous models into:

- General Adversarial Networks (GANS)

GANs are an emerging technology for both semisupervised and unsupervised learning and are composed of the i) generator and ii) the discriminator. The discriminator has access to a set of training images depicting real content. The discriminator aims to discriminate between "real" images from the training set and "fake" images generated by the generator. On the other hand, the generator generates images as similar as possible to the training set. The generator starts by generating random images and receives a signal from the discriminator whether the discriminator finds them real or fake. At equilibrium, the discriminator should not be able to tell the difference between the images generated by the generator and the actual images in the training set; hence, the generator generates images indistinguishable from the training set (Elgammal et al., 2017).

- AutoRegressive Convolutional Neural Networks (AR-CNN)

AR-CNN is a deep convolutional network architecture for multivariate time series regression. The model is inspired by standard autoregressive (AR) models and gating mechanisms used in recurrent neural networks. It involves an AR-like weighting system, where the final predictor is obtained as a weighted sum of sub-predictors. At the same time, the weights are data-dependent functions learnt through a convolutional network. (Bińkowski et al., 2017). These transformers are designed to process sequential input data, such as natural language, with applications towards tasks such as

translation

and

text

summarisation, as in the case of Open AI with DALLE-E.

- Transformer-based Models

A

transformer

is a

deep learning

(DL) model that adopts the self-attention mechanism, weighing the significance of each part of the input data. It is used primarily in the fields of

natural language processing

(NLP) (Vaswani et al., 2017) and

computer vision

(CV) (Brown, 1982).

Where can we see generative AI?

Beyond data augmentation, widely used in the medical field, generative AI can, just with a short paragraph of text, assist you with creating art and pictures (open AI's

DALL-E

system that enables the creation of hyper-realistic images from text descriptions), videos (Meta's

text-to-video

AI platform), AI avatars (synthesia's

text-to-speech

synthesis which generates a professional video with an AI avatar reciting your text), music (Jukebox

neural net) and much more. The magic behind most of this generative reality stands within Generative pre-trained Transformer (GPT-3) - a third-generation, autoregressive language model that uses deep learning to produce human-like texts and use the previous distinction to analyse them (Floridi, 2020). Simply speaking, we can understand it as 'text in — text out' - the model processes the text given and produces what it 'believes' should come next based on the probabilities of sequences of particular words in a sentence.

Below we can see the realistic images entirely created by DALL·E from the prompt of an ->

impressionist oil painting of an AI system having a drink at the beach

Image 1: Impressionist oil painting of an AI system having a drink at the beach

On the other hand, although mainly born as pornographic content, Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) have quickly moved into politics. Deepfake content was produced, for example, with Barack Obama's face "speaking" in front of a camera. A split screen shows Obama on the left while on the right is the renowned US actor, comedian, and director, Jordan Peele. Obama's and Peele's facial expressions and lip movements match at perfection. Thanks to generative AI, Peele's production team has digitally reconstructed Obama's face. This becomes a compelling example about how online video can be manipulated - leading to a loss of uncertainty in undermining trust in public discourse, a potential contribution of deepfakes to online disinformation (Vaccari & Chadwick, 2020).

Unfortunately, we do not only count with one example but rather with a series of ones. Recently during the ongoing war in Ukraine, a deepfake of President Zelenski surrendering was released on social media and got viral, including a fake Zelensky's Russian accent and robotic voice (see image 2) (Bastian, 2022). This time, the quality needed to be higher to be perceived as trustworthy, yet it is only a matter of time before the technology improves and becomes more deceiving. Meanwhile, this example illustrated the utilisation of generative AI as a part of Russian disinformation efforts, constituting the first documented attempt to achieve foreign political interference on a broader scale through deepfakes (Pawelec, 2022).

How does it differ from traditional AI?

Kaplan and Haenlein (2019) structure AI along three evolutionary stages: 1) narrow artificial intelligence (applying AI only to specific tasks); 2)

artificial general intelligence

(applying AI to several areas and being able to solve problems they were never even designed for autonomously); and 3) artificial superintelligence (applying AI to any area capable of scientific

creativity,

social skills, and general

wisdom). The currently mainstream sort of AI research studies “narrow AI”, focusing on the creation of solving-specific software and narrowly constrained problems (i.e, chatbots and conversational assistants such as Siri or Alexa).

A narrow AI program does not have a conscious or independent understanding of itself and what it is doing, in contrast to “artificial superintelligence” which would. Hence, it cannot generalise what it has learned beyond its narrowly constrained problem domain. For example, a narrow-AI program for diagnosing kidney cancer will always be useless for diagnosing gall bladder cancer (though humans may use the same narrow-AI framework to create narrow-AI programs for diagnosing various cancers) (Goertzel, 2007).

Development of artificial superintelligence would mean that a machine would require an intelligence equal to humans; it would have a self-aware consciousness that can solve problems, learn, and plan for the future, something that, according to Alan Turing's test (1950) would only be possible by evaluating if a machine's behaviour can be distinguished from a human. For example, suppose the "interrogator" from the Turing test seeks to identify a difference between computer-generated and human-generated output through a series of questions. If the interrogator cannot reliably discern the machines from human subjects, the machine passes the test. However, if the evaluator can correctly identify the human responses, this eliminates the machine from being categorised as "intelligent". Doubts arise when we ask ourselves if we could differentiate, in the case of GANs, what is “real” from what is know not.

A similar experiment can be associated with The Chinese Room from Searle (1980), which entails that a digital computer executing any sort of

program

cannot have a

mind

on it’s own, nor a truthful understanding of how things work in its surroundadings and as a result, lacks of human-like consciousness. Searle, moreover, refute the possibility of what we calls strong AI - “the appropriately programmed computer with the right inputs and outputs would thereby have a mind in exactly the same sense human beings have minds” (Searle, 1999). The definition, depends on the distinction between simulating a mind and actually having a mind. Searle writes that “according to Strong AI, the correct simulation really is a mind. According to weak AI, the correct simulation is a model of the mind” (Searle, 2009, p. 1 ). The question Searle wants an answer for is: is a machine really able to "understand" the Chinese? Or is it merely imitating the ability to understand the language? Searle would argue that the first position is "strong AI" and the latter "weak AI". This experiment remind us about long debates on artificial agents focused on the capacities of AI, as for example intentionality and agency. But also touches upon mind philosophy roots regarding the mind-body dualism, and, what is really means to be consciouss. In the last section of this blog, we will argue, through the Actor-Network Theory (ANT), that it does not necessarily matter if an actor is human or non-human, as they all play a crucial role in shaping the social system and its organization.

Challenges of Generative AI

Until now, fake news and its negative consequences have implied mainly textual content. However, new technologies constantly raise new challenges. One of these is the Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), a class of deep neural networks model developed in 2016 by Ian Goodfellow capable of creating multimedia content (photos, videos, audio), run by software that is also freely available and simulates accurate content with extreme precision. For example, if trained on a face, GANs can make it move and speak in a way hardly distinguishable from an actual video. Furthermore, these powerful technologies can produce a "self-reenactment" video that reconstructs a speaker's facial expressions in real-time (Rössler et al., 2018). Unfortunately, these techniques lead to the so-called deepfakes, as we have seen with Obama's and Zelensky's deepfake examples.

A study by Floridi (2022) points out ethical questions arousing how GPT-3 is not designed to pass the Turing test, although Turing predicted in 1950 that by the year 2000, computers would have passed it. Turing's prediction is far wrong. Today, the Loebner Prize is given to the least unsuccessful software trying to pass the Turing Test (Floridi et al., 2009). GPT-3 does not perform any better with the Turing Test. Having no understanding of the semantics and contexts of the request but only a syntactic (statistical) capacity to associate words. This study also showed GTP-3 ethical repercussions as the technology is based on previous experiences and thus "learns" from (is trained on) human texts. When asking the model what it thinks about black people, it reflects some of humanity's worst tendencies. After running some tests on stereotypes, GPT-3 seems to endorse them regularly (by using words like "Jews", "women", etc. (LaGrandeur 2020)).

The Benefits of Generative AI

Still, after the above-mentioned repercussions of GTP-3, GANs can also generate multiple socially-acceptable trajectories, "good behaviours", if correctly trained. According to

Gartner

(2021), Generative AI, in its list of major trends of 2022, highlighted that enterprises could use this innovative technology in two ways. Firstly, by enhancing current innovative workflows together with humans, for instance, by developing artefacts to aid better creative tasks performed by humans. Secondly, by helping function as an artefact production unit by neccesiting little human involvement (only requiring setting the context, and the results will be generated independently). These are great news as we tend to think that job loss and automation will likely be a threat, but rather, people whose jobs still consist of writing will be increasingly supported by tools such as GPT-3. This means that accelerating a mere task, such as cut & paste, will likely, contribute to being better at other tasks, such as prompt & collate (Elkins & Chun, 2020). We will, ultimately, have to see this tool not as a threat but rather as a reminder to write "intelligently" and save us an avalanche of time. For those who see human intelligence on the verge of replacement, these new jobs will still require a lot of human brain power, just a different application of it (Floridi, 2020).

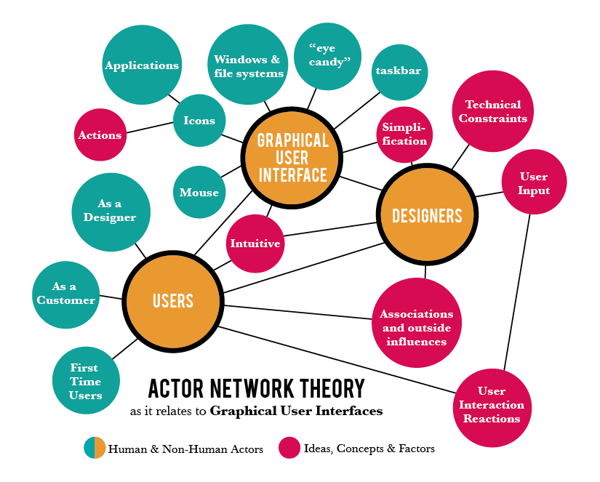

An Actor-Network Theory (ANT) Approach

Actor-Network Theory (ANT) by Bruno Latour (1987) and Woolgar (1986) is a theoretical and methodological approach developed to account for the relational nature of the social, where the social is not reduced to human social relations but includes any interactions among

actors

in a wide variety of settings. Actors in ANT go beyond individual people or groups of people. ANT considers the exchange of ideas, opinions, and information inside the social system, technical objects or artificial agents like generative AI GANs equally important. In revealing the complexities of socio-technical environments' social, material, cultural, or political dimensions, ANT emphasises the

relations

between the actors. As we have previously seen with the example of Obama and Zelensky, GANs are mainly used to create media simulating human beings conveying politically-relevant content. In this way, artificial agents created by GANs are proper actors in the social system, as they can modify another actor's beliefs (e.g. a human social media user) and change the social system's networks of relations.

Image 2: What is Actor-Network Theory by man.sudimecomptechpo.tk

The central idea of ANT is to investigate and theorise about how networks come into being, to trace what associations exist, how they move, how actors are enrolled into a network, how parts of a network form a whole network and how networks achieve temporary stability (or conversely why some new connections may form unstable networks) (Cresswell et al., 2010). In the ANT's theory of translation, the artificial actor (GANs-generated) could be involved and become an active spokesperson of a network (as a deepfake of Zelensky leading the entire network of actors supporting the Ukrainian resistance to surrender). This will, mislead and probably harm online civic culture by adding to an atmosphere of uncertainty about truth and falsity, which, in turn, reduces confidence in online news (Vaccari & Chadwick, 2020).

Drawing from various theories and phenomena, such as motivated reasoning, which refers to biases that lead to decisions based on their desirability rather than an accurate reflection of the evidence (Kunda, 1990), researchers have already identified a few specific individual variables that may motivate the person to believe misinformation he/she is exposed to. These include, but are not limited to, minority status, belief in conspiracy theories, and low trust in science, media, government, and politics (Roozenbeek et al., 2020). Previous research has also explored the role of cognitive abilities and other related variables. These studies have revealed that particularly education, reflective thinking (e.g., as measured with the Cognitive Reflection Tes (Sirota & Juanchich, 2018), and 'bullshit receptivity' are consistently associated with processing misinformation. If current fake news enables this, then GANs hyperrealism might worsen this situation. Nonetheless, it is to note that research explicitly focusing on the association between individual differences and propensity to trust GANs-generated content is much less common and thus just starting to emerge (Ahmed, 2021).

In this blog post, we discussed generative AI and, specifically, a branch of it, namely Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs). We concluded that they, on the one hand, could harm democratic societies (as in the case of Zelenzky) by decreasing trust among citizens. On the other hand, they also have the potential to generate multiple socially-acceptable trajectories, "good behaviours", if correctly trained. In order to prevent GANs from harming digital democracy, we must rapidly study and regulate their impact across all networks, as ANT suggests.

References

Ahmed, S. (2021). Fooled by the fakes: Cognitive differences in perceived claim accuracy and sharing intention of non-political deepfakes. Personality and Individual Differences, 182, 111074. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.111074

Ballard, D. H., & Brown, C. M. (1982). Computer vision. Prentice Hall.

Bastian, M. (2022). Möglicher Selenskyj-Deepfake: Miserabel und dennoch historisch. NMixed, 17 March. Available at: https://mixed.de/selenskyj-deepfake-miserabel-und-dennoch-historisch/ (Accessed 25 April 2022).

Bińkowski, M., Marti, G., & Donnat, P. (2017). Autoregressive Convolutional Neural Networks for Asynchronous Time Series. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1703.04122

Cresswell, K. M., Worth, A., & Sheikh, A. (2010). Actor-network theory and its role in understanding the implementation of information technology developments in healthcare. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6947-10-67

Elgammal, A., Liu, B., Elhoseiny, M., & Mazzone, M. (2017). CAN: Creative Adversarial Networks, Generating "Art" by Learning About Styles and Deviating from Style Norms. arXiv. https://doi.org/https://arxiv.org/abs/1706.07068v1

Floridi, L. (2020). GPT‐3: Its nature, scope, limits, and consequences. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3827044

Goertzel, B. (2007). Human-level artificial general intelligence and the possibility of a technological Singularity. Artificial Intelligence, 171(18), 1161-1173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.artint.2007.10.011

Haenlein, M., & Kaplan, A. (2019). A Brief History of Artificial Intelligence: On the Past, Present, and Future of Artificial Intelligence. California Management Review. https://doi.org/10.1177/0008125619864925

High-Level Independent Group on Artificial Intelligence (AI HLEG). (2019b).

Policy and investment recommendations for trustworthy Artificial Intelligence. https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/news/policy-and-investment-recommendations-trustworthy-artificial-intelligence.https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119471509.w5GRef225

Kurzweil, R. (2005).

The Singularity is near: When humans transcend biology. Penguin.

Latour, B. (2007). Reassembling the social: An introduction to actor-network-Theory. OUP Oxford.

Latour, B., & Woolgar, S. (1986). Laboratory life: The construction of scientific facts. Princeton University Press.

Pawelec, M. (2022). Deepfakes and democracy (Theory): How synthetic audio-visual media for disinformation and hate speech threaten core democratic functions.

Digital Society,

1(2).

https://doi.org/10.1007/s44206-022-00010-6

Vaccari, C., & Chadwick, A. (2020). Deepfakes and disinformation: Exploring the impact of synthetic political video on deception, uncertainty, and trust in news. Social Media + Society, 6(1), 205630512090340. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120903408

Vaswani, A., Shazeer, N., Parmar, N., Uszkoreit, J., Jones, L., Gomez, A. N., Kaiser, L., & Polosukhin, I. (2017). Attention Is All You Need. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1706.03762

Searle, John (1999),

Mind, language and society, New York, NY: Basic Books,

ISBN

978-0-465-04521-1,

OCLC

231867665

Searle, John (2009), "Chinese room argument",

Scholarpedia,

4

(8): 3100,

Bibcode:2009SchpJ...4.3100S,

doi:10.4249/scholarpedia.3100

Leslie, I. (2018). PERPETUAL ENMITY.

RSA Journal,

164(2 (5574)), 38–41.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/26797915

Leave us a message!

We will get back to you as soon as possible.

Please try again later.